Almost every Rusty Blackbird that I see in the eastern United States is in flight, so the simple trick is to look up. In order to do that you need to know what to look for: I use sound to know when to look, then look for flying blackbirds that are solitary or in small groups, with long wings and long, club-shaped tails.

Use your ears

First, listen for a slightly different call. All of the blackbirds and grackles give a low harsh check or tuk call in flight. In Red-winged Blackbird this is a relatively simple and unmusical chek, like hitting two twigs together. Rusty Blackbird’s call is more like chook, it has more complexity and depth. Rusty’s call is slightly longer, slightly descending, and with a bit of musical tone. It reminds me vaguely of the harsh chig call of Red-bellied Woodpecker.

These differences are subtle and not easy to pick out, and there is a lot of variation in the calls of Red-winged Blackbirds. Distinguishing Rusty Blackbird by call is definitely an advanced skill, but by paying attention to the various check sounds of blackbirds you can learn to hear the differences. When I hear a Rusty-like call I still like to see the bird to confirm that it also looks like a Rusty, but call is how I know when to look up and the best way to find a potential Rusty, and with a little bit of practice you should be able to use sound in that way.

The song is much more distinctive, and is often given by flying birds even in the fall and winter. It is a short jumble of creaking or gurgling, ending with a high thin whistle – inconspicuous but very distinctive.

Recordings at Xeno-Canto are here: http://www.xeno-canto.org/species/Euphagus-carolinus

Blackbirds do not all flock together

Rusty Blackbirds do not mingle freely with Red-wingeds, even in flight. They are usually seen flying in singles and small groups, sometimes joining larger flocks of other species but usually just along the edges and soon separating. When you hear a Rusty-like call, sifting through a dense flock of Red-wingeds is not worth the time. Instead, look around the edges of a flock or look for a few blackbirds on their own.

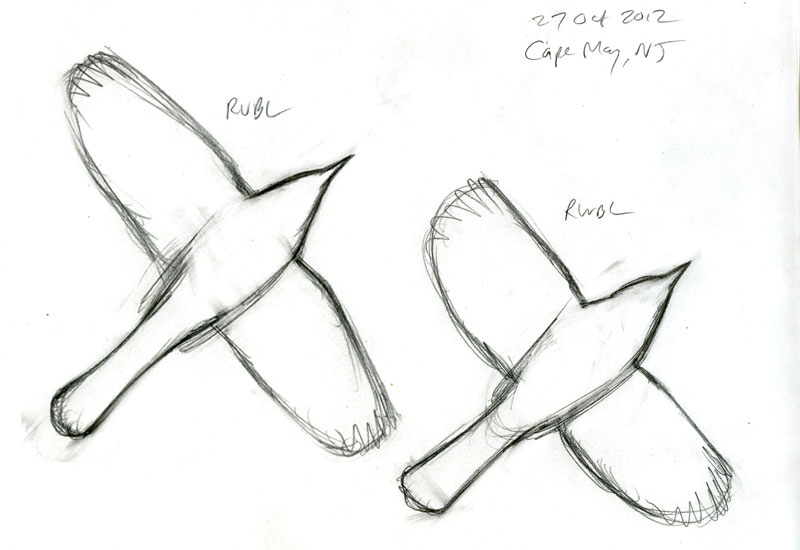

Shape is the key

Color is usually no help in identifying flying blackbirds. Most are simply dark silhouettes against a bright sky. Even when lighting is good and colors can be seen the differences are simply too subtle. Distance can blur the streaked pattern on a female Red-winged, or lighting can enhance the rich rufous tones, making it appear very much like a Rusty Blackbird.

The red coverts on a male Red-winged Blackbird are distinctive, and are never duplicated by Rusty. Similarly, if you are close enough and the lighting is good you can see the pale eye of a Rusty (just make sure you’re not looking at a grackle). But other than that there is no reason to look at color, you should focus on shape and proportions.

Compared to Red-winged Blackbird look for:

- longer tail with club-shaped tip

- longer and relatively narrow wings

- shorter head and thin bill

The overall impression is of a more elongated, sleeker bird, with long tail, long wings, pointed head and streamlined body. The wingbeats seem a little slower and flight more buoyant. If you want to focus on one thing then tail shape is probably the single best feature to study, but tail shape alone is not enough to identify this species. If you can combine call and shape, then you should be able to make a very confident (even if subjective) identification. If you can hear the song or see the pale eye, then you’re all set and you can make a more objective identification of Rusty Blackbird in flight.

Great post. Any tips for Midwesterners who might also be dealing with Brewer’s Blackbirds?

And if you happen to be watching a flock of Common Grackles, take time to study their harsher, more strident “chack” call notes. For me, I think that the Rusty contact call lies in the middle of the spectrum between the harsher grackle and the softer Red-winged, and I wholeheartedly agree with the “chook” /depth/complexity description for Rusties.

Your experience that “almost every Rusty Blackbird I see… is in flight” certainly is not the same as that of many other observers. The largest number of Rusty Blackbirds I have seen is in winter, on the campus of Mississippi State University (where I was a student for 4 years). They would feed in the open under oak trees on the campus, foraging for acorns in mixed flocks with Common Grackles, and were easily studied and easily distinguished from grackles. I’ve also seen many on the breeding grounds (which are mostly in Canada), and there they are mostly seen feeding on or near the ground, usually at the edge of a pond or swamp, or in the top of a conifer.

I do agree that, apart from the mixed flocks with Grackles, Rusties are often found by themselves, alone or in small groups, not with other blackbirds. When they do flock with other blackbirds, it’s often with Red-wings.

The toughest identification challenge is between Rusties and Brewer’s, which can be found together in the western and even central U.S. and Canada. Rusties have distinctly different songs and even call-notes from Brewer’s, which helps in identification.

I concede that identifying a Rusty seen only in flight would be tricky, but I’ve almost never had to do that in hundreds of sightings of this species, from Alaska to Alabama!

Pingback: Creature Feature: Rusty Blackbird - Columbus Audubon

Pingback: Creature Feature: Rusty Blackbird | Columbus Audubon