A pale and grayish female bluebird found in North Carolina recently (March 2012) provided a very interesting identification challenge. The plumage colors were a good match for a typical female Mountain Bluebird, and that is how it was first identified. North Carolina has only one previous report of Mountain Bluebird, so this bird received a lot of scrutiny. On closer inspection the color was not quite right for Mountain, and the shape seemed more like the expected Eastern Bluebird. A lengthy discussion on the ID-Frontiers listserve eventually came to a consensus of an abnormally colored Eastern Bluebird.

I agreed with the consensus, but it was mostly a subjective interpretation of shape and proportions, and I wanted to learn if the bird could be identified more objectively. I had a chance to check specimens at Harvard’s MCZ, along with a lot of photographs on the internet, and found a few things that, I think, confirm the identification as Eastern Bluebird.

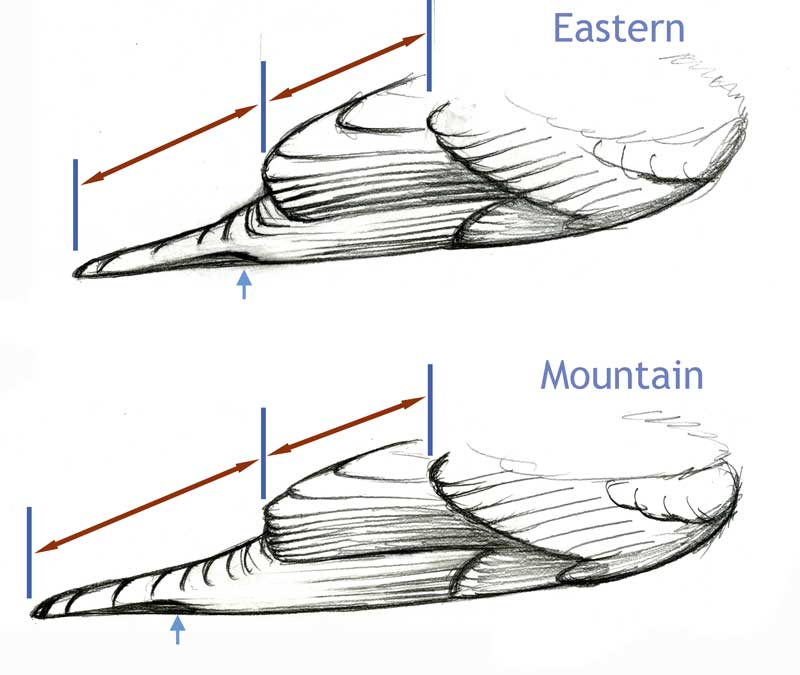

It has long been known that Mountain Bluebird has a longer primary projection than Eastern, with no overlap in measurements, but Eastern has a very long primary projection for a songbird, and the difference can be hard to judge. I found that comparing the length of the primary projection to the length of the folded secondaries beyond the scapulars and greater coverts made things easier. On Eastern Bluebird these two lengths are about equal, while on Mountain the primary projection is obviously longer than the secondaries.

In addition, the length of the exposed tail beyond the primary tips is quite different: about equal to the length of the primary projection on Eastern, but on Mountain the exposed tail is much shorter than the primary projection.

Both species have three emarginated primaries, easily visible in good photos on the lower edge of the folded wingtip. On Eastern these fall just beyond the tips of the tertials, and on Mountain they are about halfway between the tertial tips and the tips of the primaries.

Bill shape is also distinctly different, much thicker on Eastern, and Eastern has obvious yellow on the gape that is lacking or very inconspicuous on Mountain.

Head shape is variable depending on posture, but Eastern consistently has a high forehead and very rounded crown, while Mountain has a lower forehead sloping up to a peak on the rear crown.

In all of these features the North Carolina bluebird fits Eastern, and must be a female Eastern with pigment abnormalities, perhaps lacking the reddish brown melanin that would normally be responsible for the reddish breast and a lot of rich gray-brown colors on the wings and back.

Links

- The best photos of the tricky North Carolina bluebird are here: http://www.carolinabirdclub.org/gallery/Derb_Carter/mobl.html

- Details of North Carolina’s previous report of Mountain Bluebird here: http://nature123.net/ncbirds/view.php?sort_order=3130

- Discussion of this bird on ID-Frontiers begins here: http://listserv.arizona.edu/cgi-bin/wa?A2=ind1203C&L=BIRDWG01&P=R3338&I=-3

- For more on melanin pigment deficiencies see my post here: https://www.sibleyguides.com/2011/08/abnormal-coloration-in-birds-melanin-reduction/

Interesting. Does anyone know how the wing structure of the Western Bluebird fits into this?

I was surprised to discover that Western Bluebird is essentially intermediate between these two species – a longer primary projection than Eastern and emarginations fairly far beyond the tertial tips.

I was one of the few to see the NC bluebird and I took the photos you link. Two things were obvious in the field and apparent in the photos. The bird lacks any of the chestnut coloration below of Eastern Bluebird, which you note is pigment-based, and can be explained by a pigment anomaly. Also apparent in the photos, and even more apparent in the field, the blue of the wings, rump and tail was the cyan blue of Mountain Bluebird and not the much deeper blue of Eastern. All references I could find state the blue color is not pigment based but from light reflection on feather structure. So if this is Eastern, are there both pigment and feather structure anomalies to explain both the lack of chestnut and the shade of blue?

Hi Derb, First, thanks for your photos of this very interesting bird, which were instrumental in sorting this out.

The answer to your question is “yes”. Blue color in feathers is structural, and my (limited) understanding is that melanin is a key component of that structure. Given that, it makes sense that a lack of melanin in the feathers would also affect the blue color, so the overall pale gray color and the odd shade of blue could have the same root cause.

This was an interesting discussion and the question that comes to mind is whether older extralimital Mountain Bluebird records might need to be re-examined in light of this bird (depending on availability of photos of course). One might speculate that the wing structure differences are an evolutionary trait – the most obvious choice would be adaptation to habitat with Mountain Bluebirds being more open country birds than Eastern Bluebirds.

I don’t know whether you’ve read the 2006 article by Shawkey and Hill on the role of melanin in producing the “blue” in feather color in The Journal of Experimental Biology. But they suggest a change in hue as well as a change in intensity. I’m not sure that the Fayetteville bird shows this.

Thanks Mike, I had not seen that paper. I can’t say whether there’s a change in hue, but the intensity of color is much lower than a normal female bluebird, and that fits. The Steller’s Jay studied in Colorado was essentially white, lacking all melanin in the feathers. This bluebird still has some melanin (grayish color) and maybe that’s enough to maintain the color a little better?

Hi David,

Let me be clear, I think the bird is a female, but it occurs to me I am relying solely on the plumage (i.e. a lack of both deep blue on the upperparts, and orange on the breast) to do so. Perhaps I am unwise in this particular case! If a lack of melanin can reduce or eliminate these colors, as seems to be the case, does it rule out a male Eastern Bluebird? Can we be certain of it being a female Eastern Bluebird by anything other than plumage features, which we all agree are “off” for an Eastern Bluebird?

Interesting idea! One point in favor of female is that the blue color shows most strongly on the wings and tail, just like a normal female bluebird. If this was a male and the melanin reduction was uniform over the whole body, then the blue color should be more or less uniform on the upperside. There are some assumptions in there, but at least it leans towards female.

It is interesting that primary projection on the NC bluebird is one of the characters that inclined me toward Mountain Bluebird. It appeared long in the field and, while not as long as some Mountain photos, I thought fairly long in my photos of the bird. Out of curiosity, I enlarged four of my photos on the screen and measured in millimeters and compared the secondaries and primaries per your approach. I got a range (given photo angle and probably other factors) of primaries 127-130% of the length of the secondaries. I then have to decide if this “about equal” or “obviously unequal.” I did the same exercise with your illustration of a Mountain Bluebird wing and the primaries are 144% of the length of the secondaries. With this as a reference, and recognizing it is only an illustration, I would conclude the primaries are somewhere between “equal” and “obviously unequal” in length compared to the secondaries, and somewhat closer to the “obviously unequal” end. The primary emargination in my photos is clearly closer to your illustration of Eastern Bluebird.

Thanks for testing that. I guess the primary projection measurements are still a bit subjective, since Eastern is “a little longer than the secondaries” and Mountain “much longer”. I would put more weight on the position of the emarginations, of course, because that supports my conclusion 😉

How wonderful to have such great pictures of this bird!

Is it just me, or does the shot of the aberrant bird in such close proximity to a male Eastern Bluebird argue in favor of the Eastern hypothesis for the odd one, on the basis of behavioral clues?

I would think it might at least argue in favor of calling the anomaly a female!

Would sure be wonderful if this bird ended up nesting somewhere observable.

Some vagrant Mountain Bluebirds in the east have integrated pretty well into flocks of Easterns, so that doesn’t tell us much, especially in a single photo. Watching the behavior over a longer period might give some sense of whether it was male or female, and in any case, as you say, it would be a very interesting bird to watch.

Thank you, David. That was but one of many things I am unaware of!