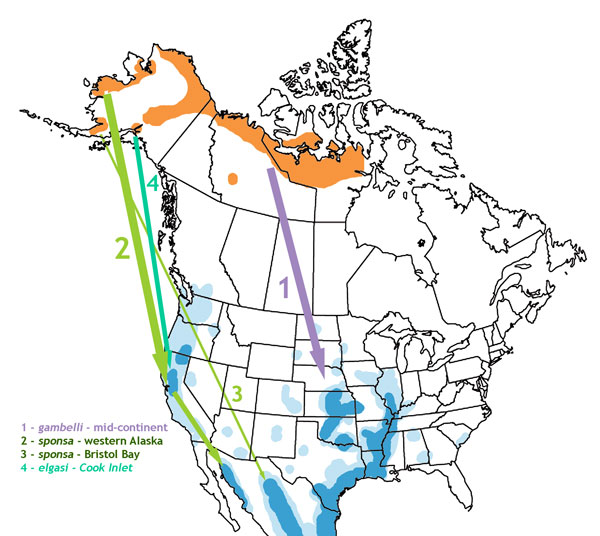

The Greater White-fronted Goose (Anser albifrons) occurs throughout much of North America, but is found in largely disjunct populations. Only two North American subspecies are listed by Ely and Dzubin (1994), four by Pyle (2008), but five well-defined “population units” have occurred in North America, and there may be more. Banks (2011) recognizes four of these groups as subspecies, proposing one new name and revising some of the existing names. His nomenclature is followed below.

Before we can begin to sort out the identification of subspecies, it is important to understand how the populations interact during the year – which ones are separate and how isolated they are.

Named populations breeding in North America

Greater White-fronted Goose (Tundra) Anser albifrons gambelli (aka. frontalis)

1 – The most abundant group in North America, this subspecies nests along the Arctic coasts from Canada to northern Alaska. The sparse breeding populations in central Alaska and in the Canadian Taiga have been separated in the past as true gambelli (averaging larger and darker), with Tundra breeders being called frontalis (averaging smaller and paler). All are considered by Banks to be gambelli, but these southern breeders are poorly-known. All of these birds winter in mid-continent and band returns show almost no mixing with other populations.

Greater White-fronted Goose (Pacific) Anser albifrons sponsa (formerly part of frontalis/gambelli)

2 – Western Alaska – Birds from western Alaska winter along the Pacific coast from California to western Mexico. Distinguished from other subspecies by average smallest size, and by range.

3 – Bristol Bay lowlands, southwestern Alaska – These birds winter almost entirely in the highlands of Chihuahua, central Mexico, where they mix with smaller numbers from other populations. These birds may average slightly larger and darker than group 2, but differences are slight and unconfirmed.

Greater White-fronted Goose (Tule) Anser albifrons elgasi

4 – The very small population nesting in Cook Inlet, Alaska, and wintering in the Sacramento and Suisun marshes of central California, has been named A. a. elgasi and is commonly known as Tule Goose. It averages largest and darkest of all subspecies (and winters alongside the smallest – sponsa), and is more likely to show a yellowish orbital ring. In winter it tends to be found in wooded ponds and small marshes, while the more abundant sponsa feed in agricultural fields. Some individuals stand out as being beyond the range of variation in sponsa, but most are very difficult to identify.

Populations breeding outside North America

- Greater White-fronted Goose (Greenland) Anser albifrons flavirostris

Breeding and increasing in Greenland, winters mainly in Ireland and Britain, but a few each year wander to eastern North America. Assessing North American records is complicated by the difficulty of identification, and an over-emphasis on bill color for ID has led to many dubious claims of Greenland birds.

- Greater White-fronted Goose (European) Anser albifrons albifrons

Not recorded in North America, but it is a potential vagrant from east or west. Some recent research suggests that two subspecies could be named, based on differences in body size and winter range.

Conclusion

Currently named subspecies are not the best guide to understanding variation in Greater White-fronted Goose. Observers should look for differences between the known “population units” described here, and it’s possible that field identification criteria will emerge from careful study.

References

Banks, R. C. 2011. Taxonomy of Greater White-fronted Geese (Aves: Anatidae). Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 124: 226-233

Ely, C. R. and A. X. Dzubin. 1994. Greater White-fronted Goose (Anser albifrons), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/131

Pyle, P. 2008. Identification Guide to North American Birds: Part II. Slate Creek Press.

Reid, M. Online: http://www.martinreid.com/Main%20website/gwgo.html

This is a subject that I spent quite a lot of time investigating more than ten years ago, and I placed some comments/discussion on this web page:

http://www.martinreid.com/Main%20website/gwgo.html

There I list all the relevant references that I could locate up until 2003 (I’d appreciate getting references of published material since then).

Although I am going from memory and it was quite some time ago, I recall two things:

1) The valid spelling is “gambeli”, not “gambelli”; this was no doubt due to a spelling error of Gambell’s name in the description published by Hartlaub (1852) – but to my knowledge no ICZN-approved correction has been made, thus it remains “gambeli”.

2) The name gambeli only applies to the birds described by Hartlaub from the Old Crow Flats area of Alaska; the Cook Inlet birds were described only recently (1990?) and separately named elgasi in honor of the person who to-date has published the only work done on gambeli on its breeding grounds (Elgas, 1970). One might argue that these two forms are indistinguishable in the field and even should be merged, but unless I’ve missed something recent, they have separate subspecific names.

I remain very interested in these taxa, and would greatly appreciate any updates on their status/distribution – published or anecdotal – thanks.

PS more recent pics from Texas are here:

http://www.martinreid.com/Main%20website/gwgo10.html

Hi Martin, and Thanks. Updates just now to text and map should fix these issues. Let me know if you notice any others, and I’ll try to find time to dig into it a little more soon.

Thanks for attacking this issue so promptly, David. I’m still a bit confused about distribution of the yellow circumorbital ring in the various populations. I have photographs of two very brown individuals wintering in Arizona which show this feature, but I’m having difficulty in assigning them to the proper population. One of them looks good in other ways (size, bill size, sparseness of the black belly markings, etc) for a Cook Inlet bird, at least insofar as I understand the literature. The other…not so much.

Pete, I’ve seen yellowish orbital rings on at least a few birds in Texas, so I don’t think that has much value as a field mark. Just to make an educated guess, based on range the Arizona birds are likely to be the Bristol Bay “frontalis”, which is said to be slightly larger and browner than the typical frontalis.

To speculate further, I suspect there will prove to be a sparsely-distributed population of taiga breeders across northwest Canada that are variably slightly darker than the tundra birds and nest slightly farther south. The Cook Inlet elgasi birds might be distinctive, at least when they are seen on their wintering grounds in CA alongside the western Alaskan frontalis. But farther east a vagrant elgasi would probably just blend in with gambeli from the Canadian taiga or Bristol Bay “frontalis”.

I have seen small body size whitefronts with larger whitefronts in Louisiana. And have seen one large whitefronted goose with the white patch extended past the eye.

Hi David! Just asking to make some adjustments to this article about the Greenland subspecies. The Greenland subspecies has a orange bill unlike the other subspecies which have a pinkish bill.

Hope this help! I am a big fan of your books!