Not really. Only under ideal conditions and with reference to location.

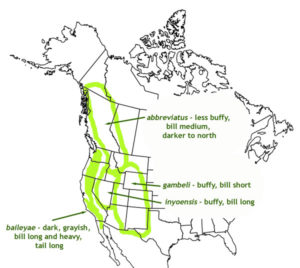

Mountain Chickadee is found throughout much of the montane coniferous forest of the west, and up to seven subspecies have been described and named. These were sorted by Behle (1956) into Rocky Mountain, Great Basin, and California groups which differ in a complex mosaic involving tail length, bill length and thickness, flank color, back color, and eyebrow width.

This variation has been getting more attention since some recent DNA studies have found a significant difference between Pacific birds (P. g. baileyae group) and Interior birds (P. g. gambeli group) ((Note that DNA samples are from the southern parts of the range, where populations are separated geographically. Sampling in the northern parts of the range where the two populations presumably intermix is critical to a full understanding of this situation)), and a proposal currently (March 2011) being considered by the AOU Checklist committee would split the species into two.

I have looked for differences in the field over the years and have never found anything that I felt I could use to objectively and confidently distinguish one population from another. A more careful check of specimens (at the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard, March 2011) also revealed no reliable differences. I could arrange series of specimens by location and clearly see overall tendencies in color, but when I ignored location data, with overlap in all characteristics, I could not place individual specimens with confidence.

Bill shape and size

Differences are very small with much overlap between populations. I could not see any consistent differences in the specimens.

Flank and back color

These are related, and birds of the interior do consistently look a little paler and more buffy. The buff color is most obvious on the flanks and rump, but also suffuses the back. Unfortunately the differences are small, and this color seems to fade rapidly as feathers age and wear, so that there is extensive overlap in color among the specimens. When a series of specimens of each subspecies in fresh plumage are laid out there is a fairly obvious difference in the series as whole, but picking up another specimen at random and matching it to one of these series is often not possible with confidence.

Width of white eyebrow stripe

This is very difficult to see and can be misleading on specimens, which often have the head feathers distorted. Nevertheless, from specimens and from field observation it is clear that there is extensive variation in head pattern among all subspecies. The Interior populations do average slightly more white over the eye, but this overlaps extensively with Pacific populations. Forehead pattern would seem to offer a more objective and easily assessed measure of this feature, but there is no consistent difference in forehead pattern. Both groups can show a solid black line extending from the crown down to the base of the bill, or a black and white speckled area there, or a solid white band continuing across the forehead. Apparent differences in the frequency of these conditions in different subspecies (e.g. Interior birds more often have white forehead, Pacific more often black) deserve more study.

Tail length

Interior birds average slightly shorter tails than Pacific birds, but there is extensive overlap and this is not helpful for field identification.

Voice

Pieplow (2011) has already considered and essentially rejected proposed differences in song. In addition to his comments, studies have found that some variation in Mountain Chickadee song depends on context, with individuals using different song types in different situations (Wiebe and Lein, 1999). This will have to be accounted for in any study of possible geographic variation in song.

Differences in calls have never been described, but at times I have thought I perceived a slight difference in the inflection and wheeziness of “dee” notes, for example between Montana and the Sierra Nevada of California. Unfortunately this is just an impression based on a handful of observations, and an informal survey of recordings at Xeno-canto and the Macauley Library did not reveal any consistent differences, but it might be worth further study.

Summary

Differences are too small and subjective to allow confident identification of these subspecies in the field. The only situation where identification might be possible is in a region where a winter irruption brings one subspecies into the range of another. With direct comparison, and knowledge of an ongoing incursion, it should be possible to distinguish two types. If that situation occurs it would provide a valuable opportunity to learn more about identifying these two populations.

The differences in DNA are clear and significant, so further field work is definitely worth pursuing. Detailed study might reveal some difference in face pattern, or call, or some other feature that is more consistent and useful.

References

Behle, W. H. 1956. A systematic review of the Mountain Chickadee. Condor 58:51-70.

Mccallum, D. Archibald, Ralph Grundel and Donald L. Dahlsten. 1999. Mountain Chickadee (Poecile gambeli), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/453

N&MA Classification committee. 2010 proposals. http://www.aou.org/committees/nacc/proposals/2010-A.pdf

Pieplow, N. 2011. Splitting Mountain Chickadee. http://earbirding.com/blog/archives/2675

Wiebe, M. O. and M. R. Lein. 1999. Use of song types by Mountain Chickadee (Poecile gambeli). Wilson Bull. 113:368-375.

Thanks for offering this discussion. We are currently (Fall 2012) experiencing a lowland incursion Mountain Chickadees into the lowlands of western Oregon. It has been suggested that the invading birds are of the interior Rocky Mtn. form (P. g. gambeli). Those making such claims are basing their IDs on the amount with white in the lores. If I’m correctly interpreting what you’ve written above, it seems a reach to be sorting these birds based strictly on appearance.

Hi Dave, That’s correct. I could not see any consistent regional difference in head pattern either in specimens or photos. The only difference that seemed to hold up (most of the time) is the overall color, but that varies a lot seasonally and I would not trust any subspecific identification of an out of range Mountain Chickadee. Voice doesn’t really help either, the vocal differences mentioned in the AOU checklist committee proposal do not hold up.

I think the only way a subspecies of Mountain Chickadee might be identifiable is if a bird from a distant population could be seen and studied alongside birds of another, known, subspecies. But I’m not even sure such a bird would stand out.