Brown Creeper is such a familiar and easily-identified bird that few birders really study it closely. Slight regional differences in plumage and song have long been known, but recent DNA research (Manthey et al., 2010) has shown that these subtle outward differences go much deeper. (David Callahan summarizes the research at Birdwatch). There is a very strong distinction between the North American and Central American populations, and weaker differentiation of the northern birds into Eastern, Rocky Mountain, and Pacific groups

The DNA evidence alone suggests that the North American populations should be considered a separate species from the Central American birds, and since the range of that southern group extends just across the border into southeastern Arizona, this would add a new species to the list of North American birds. In addition, there are slight differences in plumage and song that distinguish the three northern groups as revealed by DNA, and if further study clarifies those differences it might lead to more splits. (Arizona has records of all four and could end up with four species of Brown Creeper on the state list!)

In the Sibley Guide I illustrated two groups — Northern and Mexican — and discussed differences in song between Eastern and Western populations within the Northern group. That now needs to be refined and expanded.

The four potential species (with simple regional names for the sake of discussion) would be:

- Eastern Brown Creeper C. a. americana group

- Rocky Mountain Brown Creeper C. a. montana group

- Pacific Brown Creeper C. a. occidentalis group

- Mexican Brown Creeper C. a. albescens group

Distribution

The breeding ranges of the three northern groups probably match the general pattern shown by other superspecies such as the “Solitary” Vireo complex or Yellow-bellied/Red-naped/Red-breasted Sapsuckers. Like those species, creeper populations probably intermix where their ranges overlap in northern areas, but the exact range limits and level of interbreeding remains to be determined. In winter all three migrate south and/or downslope to some extent, with the Eastern subspecies being the most strongly migratory and appearing regularly in the lowlands of the southwest. In fact, Monson and Phillips (1981) report that in the Arizona lowlands in winter, Eastern birds are about as frequent as Rocky Mountain birds, with Pacific birds seen very rarely there. Patten et al (2003) report that the only specimen of Brown Creeper from the Salton Sea in southern California (where creepers are rare) is an Eastern bird, and Unitt (2005) reports another specimen of Eastern Brown Creeper from the California coast at Cambria, San Luis Obispo County.

Rocky Mountain and Pacific birds are generally less migratory than Eastern, so neither should be expected far out of range, but Rocky Mountain birds might reach the coast of California in some years (Unitt reports two specimens from the Mojave Desert of CA), or might reach states just east of the Rocky Mountains. Pacific birds do wander to lowlands and other habitats adjacent to their breeding areas, with a few records across Arizona (Monson and Phillips, 1981).

Mexican populations are essentially resident, and are unlikely to be found outside of their breeding habitat in the US, but some Rocky Mountain and Eastern birds must visit the same habitat in migration and winter. Phillips et al (1964) and Monson and Phillips (1981) report that typical albescens are found in Arizona only in the Huachuca and Santa Rita Mountains, while creepers in the Chiricahua and Rincon Mountains are mixed and show a complete range of variation from typical albescens to typical Rocky Mountain montana. Studying the creepers in these mountain ranges, especially songs, may provide the key for a decision on splitting Northern and Southern populations.

Identification

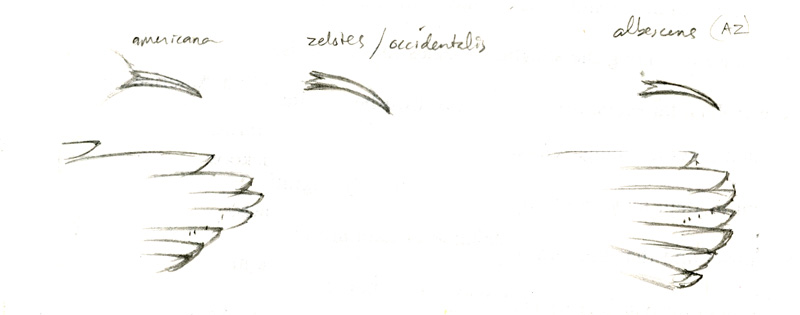

Identifying the various populations of Brown Creeper in the field will be extremely difficult. Differences in appearance are very small, subjective, and overlapping. Below is a summary of differences, but this should be taken only as starting point for future study of creeper identification. The presence of subtle brown and gray morphs within at least some populations complicates the use of overall plumage color for identification. Rump color may be one of the best single indicators, but is probably too variable to confirm an identification by itself.

Mexican is the most distinctive, and differs from the others by:

- dark overall, blackish-brown above narrowly streaked with white

- rump dark chestnut

- more extensive buffy below than other subspecies

- underparts darker sooty gray ((beware that all subspecies develop gray underparts as their plumage becomes soiled from tree bark, showing gray smudges by November and all grayish bellies by April))

- bill fairly short (shorter than Rocky Mountain birds) and may be more strongly curved

- wings short and rounded

Eastern and Rocky Mountain are very similar to each other, but Eastern differs from Rocky Mountain by:

- streaks on crown and supercilium buff-tinged (vs whitish), although most Eastern birds would be described as pale gray above, some have strong buff tones overall.

- flanks may be more buffy than Rocky Mountain or Pacific?

- bill shortest of all (vs. Rocky Mountain long-billed) and relatively straight

- may have more contrasting tertial pattern than other forms (Rocky Mountain may have least contrasting tertials of all)

Pacific birds differ by:

- overall gray and white like Rocky Mountain, but darker than either Rocky Mountain or Eastern ((Note that plumage wear has a significant effect on the appearance of creepers, making them darker as pale feather markings wear away, so a worn Rocky Mountain bird can have an overall appearance just as dark as a Pacific. Rump color is less affected by wear and therefore more reliable.))

- • rump darker cinnamon (vs pale tawny in Eastern and Rocky Mountain, dark chestnut in Mexican)

- • underparts whitish (paler than Mexican)

- • bill medium length but variable regionally

Go to next post – on variation in songs

References

Baptista, L. F. and R. B. Johnson. 1982. Song variation in insular and mainland California Brown Creepers. J. Ornithol. 123:131-144.

Hejl, S. J., K. R. Newlon, M. E. Mcfadzen, J. S. Young and C. K. Ghalambor. 2002. Brown Creeper (Certhia americana), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/669

Manthey, J. D., J. Klicka, and G. M. Spellman. 2010. Cryptic diversity in a widespread North American songbird: Phylogeography of the Brown Creeper (Certhia americana). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution: doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.12.003 http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1055790310004732.

Monson, G., and A. R Phillips. 1981. Annotated checklist of the birds of Arizona (University of Arizona Press).

Patten, M. A., G. McCaskie, and P. Unitt. 2003. Birds of the Salton Sea: status, biogeography, and ecology. (Univ of California Press).

Phillips, A., J. T Marshall, and G. Monson. 1964. The birds of Arizona (University of Arizona Press Tucson).

Unitt, P. 2005. San Diego County Bird Atlas. Proceedings of the San Diego Natural History Museum Number 39. Temucula, CA: Ibis. http://sdplantatlas.org/ge_files/pdf/Brown%20Creeper.pdf

PLEASE, can someone send an email to me explaining how to chase this Mexican Brown Creeper from our property? We have a (healthy) grape vine that it seems to scare other birds away from. Do NOT want to remove our grape vine. It is the most devious and destructive bird we have ever seen. It tears up our xeriscape/landscape as well as peck holes in our (very alive and well) Yucca Palm Trees here in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Other neighbors have stated the same. Not interested in killing it as we are getting it to go someplace else AND never return.

Please reply to: landes2012@live.com

THANKS!

That behavior doesn’t sound like a Brown Creeper, I suspect you have a woodpecker. Creepers specialize in picking tiny insects, spiders and their eggs) from the crevices in tree bark. They never make holes in trees. You can probably keep a woodpecker away from your plants by hanging something along the trunk that will move with the breeze and scare the bird, or cover it with some netting that either prevents the bird from getting access or makes it difficult to climb (but watch out for birds getting tangled).

Good Luck,

David

Pingback: Weekly Bird: Brown Creeper – Be Your Own Birder

Pingback: Again in the usA. – 10,000 Birds - PetsBlogLive

Pingback: Again in the usA. – 10,000 Birds - Specialpets

Pingback: Again in the usA. – 10,000 Birds - Petio Pets

Pingback: Again in the united statesA. – 10,000 Birds - Animal Everyday

Pingback: Back in the U.S.A. – 10,000 Birds – Petshort