A favorite activity among avid birders is speculating and pontificating about which species should be “split” into new species (and new checkmarks on the life list). Another way of stating the question is “which subspecies should be elevated to full species status?” I’ve always tried to emphasize the value of paying attention to subspecies even when they don’t “count” on a life list, but there’s only so much you can notice and it’s understandable that we all care a lot more about Island Scrub-Jay, for example, now that it’s considered a species.

It can be a little overwhelming to consider the thousands of named subspecies among the 900 or so North American bird species, so I thought I would browse the list and highlight my own picks for the subspecies most deserving of species status. I offer my top ten with comments below, feel free to disagree and make suggestions. I’ll revisit this subject periodically.

The last word on splitting and lumping species belongs to the AOU Checklist Committee. It should be understood that the the committee bases its decisions primarily on published research. It’s easy for me and others to make very definitive statements about our impressions of what is going on in the field, and I suspect many of the committee members would agree with these statements, but the committee must have a firm basis for making a decision. No matter how obvious some of these decisions might seem, any action will have to wait for published research.

My top 10 (from most to least splittable):

Willet – Eastern and Western

These two populations have no contact on the breeding grounds, and are recognizable in all seasons by structure, plumage, and voice. I can’t think of any reason to argue for maintaining these as a single species.

Whip-poor-will – Eastern and Mexican

Two populations with entirely separate breeding ranges, very different songs, differences in DNA, and subtle differences in plumage. (Nathan Pieplow of Earbirding.com reports that the AOU has now voted to split Whip-poor-will, see his post here.)

Winter Wren – Eastern and Western

Two populations differ consistently in songs, calls, and DNA, with subtle differences in plumage. This proposal has already passed an early round of voting in the checklist committee and may be official in their 2010 supplement to be published this summer. A thorough review of differences in songs and calls by Nathan Pieplow is here.

Xantus’s Murrelet – Northern (scrippsi) and Southern (hypoleucus)

Two populations with little or no breeding range overlap, no evidence of hybridization and consistent differences in plumage and voice. The status quo would seem to be the only thing in favor of keeping these as a single species.

Yellow-rumped Warbler – Myrtle (Eastern) and Audubon’s (Western)

Two populations differ consistently in plumage and calls, slightly in song. These were lumped as a single species in the 1970s, but further research and a shift in philosophy now points to full species status. They certainly seem at least as distinct as Baltimore and Bullock’s Orioles.

White-breasted Nuthatch – Eastern, Interior West, and Pacific

A three-way split of this species would be based on obvious differences in calls, and subtle but consistent differences in plumage and bill size, as well as DNA. A thorough review of the issues by Nathan Pieplow is here.

Marsh Wren – Eastern and Western

Two populations differ consistently in song, subtly in calls and plumage. These are not quite as clear-cut as the Winter Wrens, but I predict that further research will support species status.

Fox Sparrow – Sooty, Thick-billed, Slate-colored, and Red

The Fox Sparrows have been on everyone’s list of potential splits for a long time, with differences in plumage, calls, songs, and DNA. Among the reasons for inaction are lots of apparent intergrades where these populations meet, and the sheer complexity of the group. The distribution of the four groups of Fox Sparrows are similar to the sapsuckers (Yellow-bellied, Red-naped, and two forms of Red-breasted) or solitary vireos (Blue-headed, Plumbeous, and Cassin’s) but the sparrows seem more distinctive and more deserving of species status.

Spruce Grouse – Taiga and Franklin’s

Two populations differ significantly in plumage and display. There are reports of intergradation where their ranges meet in western Canada, but following the recent split of Blue Grouse into Dusky and Sooty these two deserve a closer look.

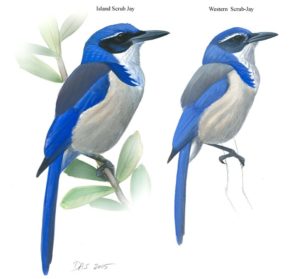

Western Scrub-Jay – Coastal and Interior (Woodhouse’s)

Two populations differentiated by plumage and voice. Biogeographically these two resemble the Oak and Juniper Titmouse split of a few years ago. A proposal to split Western Scrub-Jay recently failed an early vote in the checklist committee for want of more research in the contact zone.

And a few also-rans:

Curve-billed Thrasher – “Eastern” and Western

Suggested for splitting recently after a DNA study revealed significant differences, these two populations are distinguished by plumage and perhaps by voice. Currently under consideration by the committee for species status. I just don’t know these very well.

Eastern Meadowlark – Eastern and Lilian’s

Differing slightly in DNA, plumage, and song, these two populations have long been suggested as a potential split. Nathan Pieplow has a discussion of songs here, and there are certainly some differences, I’m just not sure that it rises to the level of species.

Savannah Sparrow – Continental, Belding’s, and Large-billed

I used to think that Large-billed was an obvious split, but after getting to know Belding’s a little better recently (see my recent blog post), I think it’s not quite so clear-cut.

Red Crossbills

With ten different call-types identified, and several studies agreeing that call types match with subtle differences in bill size and that birds of different call types rarely interbreed, this may be the most challenging and exciting field ornithology question in North America right now. The British Ornithologist’s Union recognizes three species there (plus Two-barred), and if there were only three call types (with very different bill sizes) in North America there would probably be less resistance to giving them species status here. But we have at least ten call types, and a whole range of broadly overlapping bill sizes. Like Fox Sparrows, but even more so, I think the complexity of the situation prevents action. But stay tuned!

I’m sure this post will start, or at least perpetuate, some more grassroots efforts for these splits. I guess we’ll find out how much clout the greatest field guide compiler of my generation has with the AOU!

The AOU will only look at published scientific research. Grassroots efforts by birders will have absolutely no effect.

Although KP is not an American (sub)species. A likely split would be Kentish and Snowy Plover.

Grassroots efforts by birders may not have a direct effect, but it could encourage some enterprising graduate student to take a look at some of these complexes and get the ball rolling.

Seems to me that there are lots of Euro-American splits waiting in the wings in addition to Kentish-Snowy Plover. The Herring Gulls and the Black Scoters seem to be fairly straight forward and already accepted by the BOU.

What’s the current thinking on the Mexican subspecies of Screech Owl in South Texas? Is that a potential split or is it even less likely than the also-rans?

Nate said “Grassroots efforts by birders may not have a direct effect, but it could encourage some enterprising graduate student” – Exactly!

My intention with this post was not to try to “lobby” the checklist committee, just to point birders to the most distinctive and most interesting subspecies to watch. Simply struggling with ID issues and working out distributional patterns, birders make a lot of new discoveries that can then be investigated more formally by professional ornithologists, or the “identifiability” of a subspecies can be considered along with the formal research to make the case for species status. And you don’t have to be an ornithologist to submit a proposal to the checklist committee, anyone with the time and interest could do that.

I intentionally focused on North American splits. There are quite a few New World/Old World splits that would appear high on this list such as the Kentish Plover, Black Scoter, and maybe Herring Gull already mentioned, as well as Common Moorhen, Mew/Common Gull, Black Tern, etc.

The South Texas Screech-Owls were under consideration for my list, but I don’t know enough about the contact zone and whether there’s a sharp break from typical Eastern Screech-Owls to McCall’s, or a gradual transition. And there is an opportunity for any avid birder to make a real contribution by paying attention to Screech-Owls in southern Texas…

It seems to me that Yellow Warbler and Mangrove Warbler are good candidates to be split. They look significantly different, have a different song, live in very different habitats, do not interbreed and, at least as it applies to South Texas Mangrove Warblers, do not migrate or practice limited migration.

If these pass, then it’s almost back to pre-1983!

Could the following be potential candidates for splits?

* California Cactus Wren (vocals, plumage)

* California Clapper Rail (Eastern closer to King?)

* California Raven (closer to Chihuahuan than the rest)

* California Red-shouldered Hawk (plumage, weird distribution)

* Eastern Bluebird (Arizona, same distributional pattern as the Whip-poor-will)

* Timberline Sparrow

* Nelson’s “Saltmarsh” Sparrow

* Purple Martins (Eastern/Western)

* Harlan’s Hawk

* Northern Pygmy Owl

* Bicolored Blackbird

And of course, last but not least Mexican Duck, which actually seems to be closer to Mottled than Mallard. And what’s the knowledge on the flickers and the juncos nowadays?

Here in Europe, American Herring Gull is regarded as a different species to the Herring Gull. American subespecies of Common Scoter, that I could observe in Chesapeake Bay, is considered now a separate species (Black Scoter) from the european form, and the same for the Velvet Scoter. These new species are covered in the second edition of Collins Guide by Svensson, Mullarney and Zetterström. About the crossbills, there are 4 species recognized long ago: two-barred, common, parrot and scottish.

I recently heard through the grapevine that the Whip-poor-will split, like the Winter Wren split, has been approved by the AOU Checklist Committee, and I posted about it here.

Thanks for covering this topic! I’m always fascinated by taxonomic changes, and I love the guessing game.

How about a list of potential lumps, for example Cordilleran/Pacific-slope Flycatcher. Recent publication by Rush et al. brings this split into question w/ additional unpublished data providing further support.

Interesting suggestion, I’ll work on this. The Cordilleran/Pacific Slope Flycatcher is certainly high on the list of potential lumps (re-lumps?), Thayer’s and Iceland Gulls, and Northwestern Crow are others. Caribbean Coot is off the ABA list, so not really in the picture, but the AOU still lists it as a species, and maybe they are distinctive enough where they occur in the Caribbean, but I have my doubts. And I wonder if Bicknell’s Thrush, the Solitary Vireos, and the sapsuckers are really any more distinctive than the various juncos? But then we’re into a tug-of-war over populations that just straddle the line between species and subspecies, and there is no good answer.

According to the highly acclaimed IOC, the Kentish Plover and Snowy Plover is already recognised to be a separate species supported by scientific research. I know IOC is not popular in North America but it is just a fact. 😉

Also the Winter Wren is now split such as the Common Moorhen. Source: http://www.worldbirdnames.org/updates-spp.html

Hi Gyorgy, Thanks for pointing this out. I have nothing against the IOC. On the bottom line these decisions are simply opinions, and here in North America we support the opinions of our own AOU, but it is healthy to consider another viewpoint. I notice that the IOC has also announced the split of Woodhouse’s Scrub-jay (from Western), Yellow-rumped Warbler (into four species!), and Mexican Duck (from Mallard), and Band-rumped Storm-Petrel (into at least three), which are all plausible. Kentish Plover and Common Moorhen have not been recorded (yet) in North America, so I did not include them in my list of potential splits. Along those lines I would vote for Black Tern as one of the most overdue splits of New World and Old World forms.

Greetings

Can’t argue really with the top ten, as two were nailed dead-on. Evidence for the Xantus’s Murrelet split has been long-standing, showing assortive mating at the island on which they both breed (normally). The Fox Sparrow split keeps getting shot down by the AOU despite rather extensive work already done by Zink, so I am not sure what additional data could be provided to cause the split to occur, other than a change in the AOU committee. The Spruce Grouse races have very different displays, though I guess it doesn’t stop hanky-panky in the overlap zone; still, the split would seem on par with the Blue Grouse split, as Dave mentions.

The Sav Sparrow split would likely be a split into two not three species, based on the mtDNA work by Zink: Northern Sav Sparrow (or I’d guess, Savannah Sparrow) and Saltmarsh Savannah Sparrow (God forbid– perhaps Belding’s or Large-billed would be name used). Zink found that Belding’s and LB Sav (using mtDNA) grouped together and separate from the more northerly forms.. which makes sense as these two coastal/southern taxa use saltmarsh for breeding and northern Savs rarely do. Also, there are multiple isolated populations of LB/Belding’s sparrows along the w. Baja coast that form a cline of sorts between LB and Belding Savs with the birds breeding at Magdalena Bay in sw. Baja looking fairly well half way between “standard” LB and Belding’s Savannahs.

I HATE the crossbill split (contrary to many, I admit). Genetic data are lacking to my knowledge, and crossbills (to my great surprise, as this is supposed to be genetically hard-wired) can change call-type. In the study on the Idaho birds (or maybe the SD population, can’t remember) there was mention of a small percentage of birds joining the flock and changing call type form their “original” call type to that of the group they joined. That makes me very nervous, because a small amount of gene flow across a broad area can stop full “speciation” as I understand it… One might say, “There is gene flow between RN and RB Sapsuckers,” which is true, but only in a limited area. SInce many crossbill groups are widely in contact with each other, at least intermittently, this gene flow could occur quite broadly. In any case, I think there is a lot of digging to be done there, and I might well be wrong in the end, but I just feel that this interesting complex still needs much work before the taxonomic distinctions can be truly discerned.

Finally, Russet backed and Olive backed (Swainson’s) Thrushes have recently (last year, I believe) had some nice work done using mtDNA, song, and plumage that shows there is a quite narrow hybrid zone, and that the two taxa are really pretty distinct. I think this is the only split I’d add to the David’s lists that isn’t already there. And then one wonders about Lutescent (and the Channel Island race) of OC Warbler being different from the other OCWAs, though I know of no work going on there.

In any case, the Swainson’s Thrush split and the Yellow Warbler split (Yellow vs Mangrove vs Golden or Yellow vs Golden/Mangrove) Warbler split are the only two that I’d personally add to David’s well though out list. Mexican Duck is a good runner-up, and for extra-limital birds, the Bahama YT Warbler is rather different from ours.

Cheers

Steve Mloidnow

Being a South Dakotan I am always amazed at birders when they come to see the “White-winged” Dark-eyed Junco here in the Black HIlls. They never believe the song, which CAN (not always though) be very different from the sweet trill of many Dark-eyeds.

I must say we would like our junco back. I’m sure there are many in Oregon (and environs) that would like theirs, too.

Had a ‘White-winged’ at my feeders a couple of years ago in December on a very cold snowy week.

N. New Mexico…30 miles E of ABQ.

You mention variations in “DNA” as a reason for many of these splits. However, it has been my understanding that mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) was the organelle of choice in many DNA studies of birds, and not the actual host DNA. How is this justified?

You are correct, virtually all of this research deals with mtDNA, and when I say “DNA” I’m referring to both nuclear and mitochondrial. Maybe that’s too broad, and I’d be happy to switch to some other umbrella term if there is a better one.

What about Green-winged/Eurasian Teal? It appears that AOU is the only group that does not accept their separateness. The same is true, I think, of the Green and Ring-necked Pheasants.

Since AOU accepts only published papers, these two seem particularly problematic, since it appears that everyone but AOU already considers them separate and therefor there is little reason for someone to do a paper on them. As well write a paper showing that Stellers’s and Blue Jay are separate: everybody already knows that, so what’s the point?

Hi Dan, I think in those cases the published data is ambiguous, as it is in lots of other cases. There will always be a measure of interpretation involved in whether or not to call these a species.

Ever hear the song of an Inyo Calif Towhee? They sound more like Blue Grosbeaks than Calif Towhees. It’s very impressive. Unfortunately, there’s nothing on xeno-canto nor anywhere else that I can find. I’ve got to get out there and record them sometime…

I haven’t heard that, and hope you can get a recording. I’ll be very interested in learning more.

My understandin on the DNA between the Savannak Sparrow and the Large-billed Sprrow, was that LBS was closer to theDNA of a Song Sparrow, rather than the Savannah. Am I wrong on this?

Several years ago I recall discussions about splitting Crested Caracara into “Florida” and “Texas” populations. Is there any support for this today? Is this too in need of published data?

Pingback: A Yellow Rump

Is anybody looking at Cackling Geese? The four subspecies are so clearly distinguishable, and I’ve never read an account of any hybrids.

I love birds and I love seeing new species, but I think we need to stop splitting until we start splitting humans into different species based on no range overlap, differing vocalizations and behavior, different genetic markers. I said that a tad extremely, but what I am getting at is that we need to stick to a definition of species (recognizing the fluidity of genetics and that there will be a spectrum). We are not being consistent and most of these splits, I would argue, show nowhere near the amount of variation needed for speciation. In fact, most of these splits probably are not even incipient.