The following photo has been the subject of a discussion on the ID-Frontiers listserve recently. It’s a Swainson’s Thrush, but is it the first-ever record of a melanistic Swainson’s Thrush, or just a normal bird seen in shadow?

It certainly looks dark, but it is also in the shade. Points in favor of the “shadow” hypothesis include: the pale eyering and pale breast are visible and look normally-colored, the dark gray color of the back is matched by shaded parts of a normal Swainson’s Thrush in the same photo (see below). Points in favor of the “melanistic” hypothesis include: it looks really dark, the flanks (especially below the bend of the wing) seem darker than one would expect, and Brush Freeman (the photographer) says it looked very dark in his brief views in the field.

With another Swainson’s Thrush in the photo for direct comparison, the impression of darkness becomes even stronger, but two things are happening to reinforce that impression. First, the normal-looking thrush is in dappled sunlight, so parts of it’s body show the typical brownish color and we automatically interpret the darker parts as shadow. The dark-looking bird is entirely in shadow and gives us no other reference point to judge its color. Second, the normal-looking bird is turned so we see more of the pale breast and belly, while the dark bird is turned in a way that hides almost all of the pale underside, reinforcing the impression of darkness. I think it probably is a melanistic Swainson’s Thrush, but it’s remarkable that the photos are ambiguous, and I suspect we will never know for sure.

Color Illusions

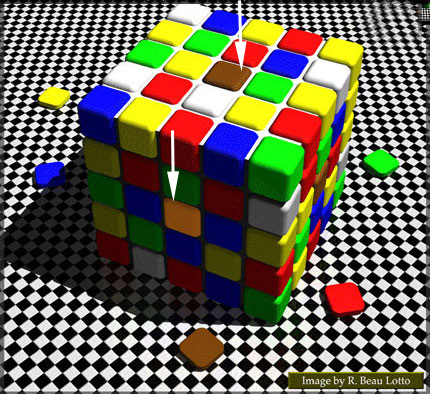

We do not perceive color absolutely, we see relative colors, and we are constantly making mental adjustments so that we can interpret the “true color” of a thing even as it is moves from shadow into sunlight, or when viewing the world through yellow or blue or rose-tinted glasses. A striking example of how we can misinterpret colors is shown by this example from the Lotto Lab.

On this cube, the two brown tiles marked with white arrows appear to be very different colors, but that is only because we expect the tile on the shaded side of the cube to be darker. We interpret the relative colors of these tiles automatically, making allowances for the brightly-lit and shaded sides so that we see the red tiles, for example, as the “same” color on the top and side of the cube, just in different lighting. When confronted by a tile that is actually the same color, it is impossible for us to overrule our brain’s interpretation of shadows, and impossible to see those two brown tiles as the same color, even when the proof is shown.

In the field, with birds constantly moving from one setting to another, it would be easy to misinterpret the conditions of light and shadow at any particular moment, and automatically “adjust” our color expectations to give a misleading result. The overall impression of a bird’s color is something we develop over multiple observations under many different conditions.

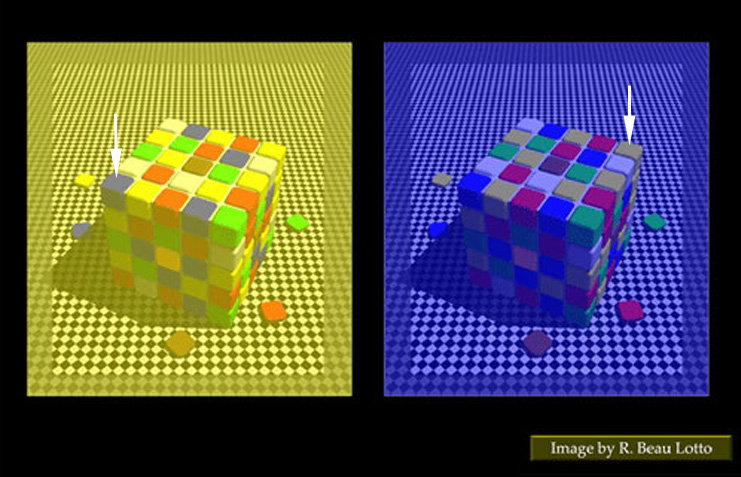

Another example from the Lotto Lab shows two different cubes, one suffused with blue light, the other with yellow light. Compare the tiles marked with white arrows.

In this case we judge the color of the plain gray tiles relative to the colors around them, and they take on a color cast opposite that of their surroundings. This is an example of the “contrast effect”, which makes cold water feel warm when our hands are cold. We are struck by the bright yellow plumage of an Orange-crowned Warbler when we see it among sparrows and dry weeds in winter, but the same bird in a field of sunflowers in August would look positively gray.

Getting back to the Texas Swainson’s Thrush, it’s clear that our perception of color is subject to all kinds of illusions. What appears to be a very dark bird may be just a normal Swainson’s Thrush in shadow and turned away from the camera. Or it may be melanistic. These two photos are the equivalent of a momentary glimpse in the field, showing the bird only under one set of conditions. Figuring out exactly what is going on would take longer views or more photos, and we may never know this bird’s true colors.

IMO, this bird are not a melanistic bird but only lack of phaeomelanins (lack of rufous tones) and look more greyish then really darker. I have made a “blur average” color on the shadow part of the body on the both thrushes and there’s the result:

[img]http://www.monalbum.ca/data/1471/comparecolor.jpg[/img]

I known that it’s impossible to have exactly the same kind of shadow in both birds (variable shadows under a tree) but it give a idea.

My two cent

Marcelo Brongo

Barcelona, Spain

Thanks Marcelo, I was using the term “melanistic” in the broad sense when I really meant something much less precise like “abnormally dark color”. You make a good point that (if this is an abnormally-colored bird) it could be missing brown pigments, causing an overall gray tone, rather than having an excess of blackish pigment. I still think it has to have an excess of some pigment to make the flanks look so dark (again, if it is abnormally-colored at all), but it could be an excess of gray and no brown.

David,

In my opinion there is no evidence here of melanism at all. I have quite a bit of photofinishing experience having worked in that industry for many years. While it is not possible to totally reverse the effects of under-exposure there is additional information to be gleaned from such images when appropriate photofinishing corrections are made and I think an attempt should always be made to try and correct colour and density errors created by improper camera exposure. While it may be very difficult, particularly for the untrained eye to find a photographs “Normal” exposure its always worth a try.

I find the images presented here to be cold (too much blue, cyan and green) and dark. When one corrects for the cold colour cast and excessive density in the images presented what is revealed (at least to my eyes) are two perfectly normal looking Swainson’s Thrushes.

That aside, your remarks about colour illusions are very interesting indeed. I am always fascinated by how variable some Old World Acrocephalus and Hippolais warblers can look during the autumn depending on the type of foliage they are moving through and whether they are in shade or in the open. It makes the task of accurately describing and also accurately photographing these birds next to impossible at times.

Regards

Michael O’Keeffe

Ireland

David,

It is nice to see that you are aware of, and making the birding community aware of the problems with color perception. I have been studying birds and color perception for some time and am amazed that this is not an issue in the natural history community (although I may be unaware papers and such). There are many references to the problem in the art world, Josef Albers “Interaction of Color” shows just how tricky judging color can be. Betty Edward’s book “Color a course in mastering the art of mixing color” is worth reading even for non-painters. In one chapter Edwards relates a story by a fellow painting teacher who set up a still life with white geometric objects and some eggs. The still life was illuminated with only a pink spotlight. The students painted the geometric shapes in pink tones but painted the eggs white because they “knew” eggs were white. This illustrates something of a problem that can be encountered when seeing birds in the field. It is possible to mentally paint birds the colors we think they should be, which is fine for birds we know well, however it may be a problem for a bird that are for some reason ambiguous. This may be something of a psychological issue, but there are many physiological reasons that our color perception may be less than “true” Margaret Livingstone’s book “Vision and Art, The Biology of Seeing” shows that in the process of seeing images are highly “filtered” as they change from photons to something we perceive as an image in the brain. The book has an excellent example of the Cornsweet Illusion which shows how difficult it is to perceive gray tones. I applaud Steve Howl’s use of the Gray Scale in identifying gulls, however understanding the Cornsweet Illusion we see that the use of a Gray Scale in the field also has its pitfalls. Color and visual perception are events that we as individuals are constantly interpreting and they are not as solid and “real” as we are led to believe.

I treated this subject, briefly, in an essay on Gray-cheeked Thrush ID:

http://cobirds.org/CFO/ColoradoBirds/InTheScope/37.pdf

Tony

The color cube illusions are fun, but not really relevant to the issue of color perception in real 3-dimensional things. Give a 3-dimensional object with a certain color and under varying lighting conditions, the observational input available to us is a 2-dimensional projection onto a screen (camera sensor, retina, or the imaginary canvas in our mind onto which it is projected), and the game is to try to infer the “true color” of the object given this 2-dimensional projection. To say that the two tiles in the cube are the same color is really saying that their projection are the same color, which is irrelevant to determining their “true color” (which is somewhat meaningless in a computer-generated image). In other words, if you reproduced those pictures using real cubes and lighting conditions, those tiles CANNOT BE the same color. Our mind adjusted based on the real 3D world’s model, and in that world, they’re not the same color.

As for the thrush ID: the second photo shows one bird in shadow and another in dappled light. Those are conditions that most humans are familiar with, and so when our mind infers colors for those subjects, it’s probably doing a pretty good job.

Probably the bigger issue at hand is that camera sensors observe differently than human sensors — especially with respect to exposure and high contrast. In that regard, Michael O’Keeffe is at least playing the right game — trying to recover the colors in a “perfect exposed” image.

I really enjoyed especially Suan Yong and Michael O’Keeffe’s comments. I would add that this potential optical illusion could very well be tested so long as conditions at the time of the photograph are available (including exact location, date, time and perhaps general weather conditions etc.). Why not put out a couple average-looking Swainson’s Thrush decoys in a similar position with similar conditions and see how it plays out to both the human eye and the camera lens. If I lived nearby in Texas, I would do it for fun.